As Southern California starts to emerge from the most destructive wildfire episode in Los Angeles history, the priority must be to continue supporting affected communities and first responders. At least 28 people lost their lives and over 16,000 structures were destroyed. Economic loss estimates to date range between $95-275 billion, with insured losses estimated between $28-75 billion. One of the costliest climate-related disasters in U.S. history comes on top of an already teetering insurance system.

Rapid climate attribution analysis for these fires so far have found that the extreme Fire Weather Index (FWI) conditions that marked the fires were made 35% more likely by human-caused climate change, driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. To understand why these fires were so destructive, it is important to understand the combination of conditions that led to the fires.

The role of climate change in the fires

First, Southern California experienced one of its driest starts to the rainy season in over 150 years. Then, an unusually powerful Santa Ana wind event developed – these are hot, dry winds that rush down from the mountains toward the coast. This particular event featured hurricane-force gusts up to 100 mph in some areas.

When these fierce winds met the bone-dry landscape, they created what meteorologist Daniel Swain called “an atmospheric blowdryer” – which once the fire ignited quickly became a blowtorch with conditions so extreme that even the most aggressive firefighting efforts, with significant advance notice and warnings, were overwhelmed. Making matters worse, the winds affected areas that don’t typically see such intense Santa Anas, catching many communities off guard.

Swain said this represents “a tragic lesson in the limits of what firefighting can achieve under conditions that are this extreme.” Four decades of data on wildfires in California and the western U.S. show that “anthropogenic climate change is the driver” behind major changing factors (increasing temperatures, dryness) that correlate with increases in annual area burned.

In a press conference, hydroclimatologist Park Williams, an expert in drought conditions, likened these multiple factors as “switches” that each had to be “on” for the fires to wreak unprecedented havoc. When asked about whether this tragic fire episode could have escalated if any of those switches were “off”, he responded by noting that any one of them could have dampened the fires – which would have turned this from a national tragedy into a mere blip.

While uncertainties exist in quantifying the effect of climate change on each of these switches, the trendlines mostly point in the direction of growing risk over time, underscoring how climate change operates through multiple pathways as a risk multiplier that is already mutating natural weather hazards into devastating compound disasters.

Climate and economic tipping points

It is worth comparing the scale of insured losses from this single climate-fueled disaster (estimated at $28-75 billion) to the $22 billion of premiums that the insurance industry underwrote for commercial fossil fuel clients last year. Munich Re – the reinsurer that issued the first warnings on climate change over 50 years ago – noted that “climate change is showing its claws” as weather catastrophes dominated over $140 billion of insured losses in 2024. As climate losses grow, this raises a question – at what point does it become the economic self-interest of insurers to align all business decisions with a 1.5 degrees Celsius climate pathway – widely considered the threshold beyond which the most extreme risks lie? And, have we already passed that point?

Insurers should study climate tipping points before it is too late to prevent worse losses. Climate-exacerbated fire risks are a concerning feedback loop that risks careening out of control: hotter and drier conditions are driving bigger wildfires which release more carbon which escalates future heat, fires, and associated losses. Scientists warn that at current levels of global heating, we are already within the uncertainty range of crossing five climate tipping points: tropical coral reef die-off, Greenland ice sheet collapse, West Antarctic ice sheet collapse, Northern permafrost abrupt thaw, and Labrador sea current collapse. Who will insure the irreversible economic consequences of crossing them? As private insurers insulate themselves from risk and retreat from communities, how will lawmakers and regulators protect their constituents?

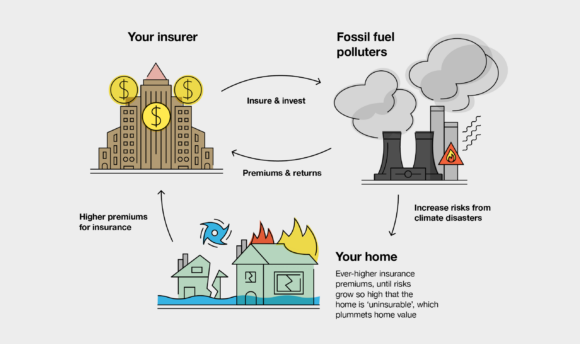

The cruel irony is that many of the same insurance companies who have been citing climate risks to justify leaving California’s market are actively fueling those risks through their fossil fuel business. Insure Our Future’s past analysis shows that a dozen companies – including AIG, Chubb, Farmers, State Farm, Liberty Mutual, and others that have restricted coverage in California – collectively have over $113 billion invested in fossil fuels and earn billions annually from underwriting fossil fuel companies and projects exacerbating climate risks.

Community centered solutions

California regulators have powerful tools at their disposal to address this growing crisis. In 2022, California’s Department of Insurance published insurance companies’ fossil fuel and green investments from 2018 to 2019. Unfortunately, nearly 3 years later, not much has changed and insurers continue to invest and underwrite fossil fuel projects. As the world’s fifth-largest economy and a major insurance market, California could require insurers to disclose and phase out their support for new fossil fuel projects as a condition of doing business in the state. Yet despite mounting evidence that climate change is making parts of California uninsurable, state authorities have not used their powers under the McCarran-Ferguson Act to address the root cause of growing climate risk: greenhouse gas emissions.

Other states are taking action. New York has introduced a bill that would ban insurers from supporting new fossil fuel projects and support communities facing climate impacts. Vermont and New York have passed “climate superfund” legislation to recover climate-related costs from fossil fuel companies rather than letting those costs fall on taxpayers and insurance ratepayers. In California, Senator Scott Wiener introduced the Affordable Insurance and Climate Recovery Act, which would shift the burden of increased insurance costs away from California ratepayers to the fossil fuel companies.

The Los Angeles fires demonstrate that we’ve entered an era where climate impacts can overwhelm even the most robust emergency response systems. The reality is that no community can expect to simply adapt their way out of the climate crisis. To give community resilience a fair chance, we must address root causes before ever-larger areas succumb to unacceptable risks driven by climate tipping points.